This

is the second post in my series on sleep and memory. Check out the first post in the series for an introduction to the four stages of sleep and early

research on the interaction of sleep and memory.

Rapid Eye Movement (REM) or

dreaming sleep is not exactly restful. Dreaming uses up energy, and our bodies

use more oxygen while in REM sleep than when we are awake! Since the purpose of

REM sleep can’t be to replenish energy, something else must be going on in the

brain. This “something else” is suspected to be the organization and

preservation of memories.

|

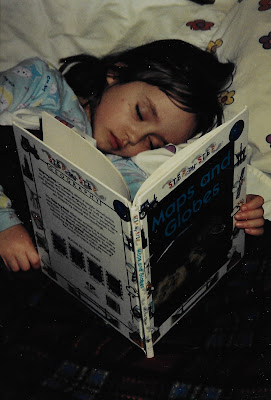

| Image by blog author. |

During childhood, 50% of

the time spent asleep is devoted to REM sleep. Childhood is also a period of

intense learning. As kids, we learn how to walk, how to read, how to make

friends, and many other valuable skills we’ll rely on our entire lives. The high

amount of REM sleep in childhood is likely crucial for remembering what we

learn as kids

In contrast, REM sleep

deprivation makes learning difficult. REM sleep deprivation during childhood

development is especially detrimental and can cause problems with the visual

system and behavioral differences that remain in adulthood. [1]

REM sleep is also linked

to efficient learning since the more REM sleep a person gets after learning the

more productively they can learn. To foster effective learning, the length and

quality of REM sleep increases after learning in children and younger adults. [2]

Getting sufficient REM

sleep improves task performance and helps people retain memories in challenging

circumstances. Here’s an example: in a study by Jeffery Ellenbogen and his

colleagues, study subjects were asked to memorize two similar lists of words.

Subjects who got normal amounts of REM sleep didn’t confuse the two lists as

much as subjects who were deprived of REM sleep. [3]

The benefits of REM sleep

for retaining memories are less prevalent in older adults. The ability to learn

and remember things decreases with age as does the duration and quality of REM

sleep. Older adults do not show the same increase in REM sleep after learning

that younger adults and children do. This is likely linked to the fact that

older adults tend to be less efficient learners than younger people.

Most of the evidence of

the role of REM sleep in memory retention I’ve discussed comes from sleep

disruption studies. Where participants are first taught a new task, told a

story, or asked to memorize a list of words. After this, the study subjects’

brain waves are monitored during their sleep. The control group are allowed to

have a normal night’s sleep, while the experimental group are woken up as soon

as they enter REM sleep, thus depriving them of only REM sleep. Then, the next

day the subject’s memory of what they learned is tested to see how REM sleep affected their memory.

The results from these

studies seem conclusive—REM sleep is crucial for memory retention! But, there

is more than one type of memory. Remembering how to ride a bike requires

different brain activity than remembering what you ate for lunch on Tuesday.

Does REM sleep help us remember all types of memories or just a few types? Do

other sleep phases play a role in memory as well? Find out in my next post.

[1] Li, Ma,

Yang, and W. B. Gan. “REM sleep selectively prunes and maintains new synapses

in development and learning.” Nature Neuroscience, vol. 20, Jan. 2017, pp. 427-437. doi: 10.1038/nn.4479.

[2] Hornung, Regen, Danker-Hopfe, Schredi, and I. Heuser. “The Relationship Between REM Sleep and Memory Consolidation in Old Age and Effects of Cholinergic Medication.” Biological Psychiatry, vol. 61, no. 6, Mar. 2006, pp. 750-757. ScienceDirect, doi: doi.org.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.034

[3] Ellenbogen,

Hulbert, Stickgold, Dinges, and S. Thompson-Schill. “Interfering with Theories

of Sleep and Memory: Sleep, Declarative Memory, and Associative Interference.” Current

Biology, vol. 16, no. 13, 11 July 2006, pp. 1290-1294. ScienceDirect,

doi : doi.org.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.024