The first loaf of

sourdough bread I made tasted good covered in melted cheese—in the way I

imagine cardboard would taste good covered in melted cheese. My sourdough bread

was dry, crumbly, flavorless, and barely edible.

What went wrong? I have a

few ideas, but before I share my hypothesis for the Great Bread Failure, let me

explain what exactly sourdough bread is.

Bread is leavened with

yeast—a microscopic fungus which breaks down carbohydrates in flour and

releases carbon dioxide and ethanol as byproducts. The carbon dioxide released

by the yeast fills the bread dough with gas and makes the dough rise, giving

the bread the fluffy texture we expect.

Most bread we make and

eat today is leavened with dried baker’s yeast—Saccharomyces cerevisiae—a yeast species specifically bred for its

leavening capability. S. cerevisiae isn’t

the only yeast that can leaven bread. Wild yeasts growing on food and on practically

every other surface can also be used to make bread—if we can catch them.

A sourdough starter, simply

made of flour and water, is the way people harnessed the power of wild yeasts

for centuries. This starter is used in place of dry yeast to make bread. Or, I

should say dry yeast is used in place of a sourdough starter, as dry yeast is a

fairly recent invention and originally all breads were sourdough.

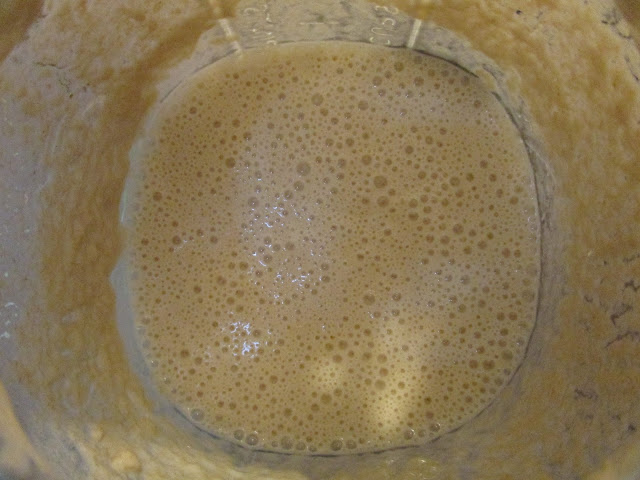

|

| My bubbling sourdough starter. The bubbles are carbon dioxide being released by the yeast. Photo by blog author. |

The water in the

sourdough starter prompts flour enzymes to break down starches in the flour

into carbohydrates that yeasts can digest. The yeast naturally found in the

flour begin to ferment these carbohydrates and release carbon dioxide, ethanol,

and a variety of other byproducts, including B vitamins and organic acids.

The yeasts in the

sourdough starter are joined by lactic acid bacteria, a type of beneficial

bacteria which lives on food and in soil. The lactic acid bacteria also ferment

carbohydrates in the flour, but the main byproducts they produce are lactic and

acetic acid. Lactic acid bacteria are responsible for the “sour” in sourdough. (To

learn more about lactic acid bacteria check out my blog post on vegetable

fermentation.)

Once a sourdough ferments

for about a week, it is ready to be used to make delicious sour bread.

Or in my case,

not-so-delicious bread. My sourdough didn’t even taste sour!

The sourdough recipe I used

called for baking soda, another leavening agent mainly used in quick breads. Baking

soda reacts with acid to release the carbon dioxide which allows the bread to

rise, but during the reaction the acid is neutralized. When I mixed baking soda

with my sourdough starter, it fizzed like a baking-soda-and-vinegar volcano

releasing copious amounts of carbon dioxide. While the baking soda helped my

bread rise faster, it also neutralized all the tasty lactic and acetic acid in

the dough, leaving my concoction decidedly un-sour and un-tasty.

|

| Baking Soda. Photo by blog author. |

The baking soda explains

why my bread wasn’t sour, but not why it was so dry and crumbly.

When I was making my

sourdough, I got a little carried away with adding whole-wheat flour.

Whole-wheat flour is very healthy, but the bran in it soaks up lots of water—more

water than I accounted for. Since I didn’t add enough water to the dough I

ended up with dehydrated and unappetizing bread.

Despite my struggle with

my first sourdough attempt, I was determined to try again, and sourdough take

two turned out wonderfully! I did not use baking soda and I used a mixture of

both whole-wheat and white flour to avoid the dehydration problem.

Why was I so determined

to repeat the sourdough experiment? One reason is because well-done sourdough

is delicious and has many health benefits, but the reason I really am

interested in sourdough is the dynamic and little-known relationship between

the yeast and lactic acid bacteria in the sourdough starter. More on that

relationship in my next post!